Issue 3, May 19, 2014

Basil Downy Mildew in 2014

A sample of basil from Wisconsin was diagnosed with downy mildew last week at the University of Illinois Plant Clinic. Basil downy mildew was a serious problem last year and, depending on the weather, we may be seeing more of it in 2014. This pathogen affects both homeowners growing a few basil plants for fresh harvest, and the producers who cultivate commercial basil in Illinois.

According to Dr. Babadoost, a professor in the Department of Crop Sciences at the University of Illinois who specializes in diseases of vegetable crops, this disease is very serious for Illinois growers. Approximately 600 acres of basil are planted in Illinois, which has become one of the leading states in basil production in the country. Basil is a high-value crop, valued between $10,000 and $20,000 per acre. While there are a number of other important downy mildew diseases, including the infamous impatiens downy mildew, basil downy mildew is host specific and will not infect other plants.

The disease was first reported in the United States in 2007. By 2009 it had reached Illinois late in the growing season. The disease is caused by Peronospora belbahri, a fungal-like oomycete (also known as a water mold). It flourishes in cooler, wet weather, so the disease is generally worst at the beginning and end of the growing season. Hot, dry weather causes the pathogen to go dormant. Symptoms first appear as diffuse yellow areas on the top side of leaves. The pathogen produces spores on the underside of leaves, giving them a dirty appearance. A hand lens can be used to look for spores and the translucent, thread-like structures that produce them. Under magnification, the undersides of the leaves appear to be covered in grey fuzz. The disease progresses quickly, with affected leaves turning brown and falling from the plant; within a few days an entire plant can be defoliated.

Underside of a basil leaf infected with basil downy mildew; clumps of spores of the pathogen give the leaf the characteristic dirty, fuzzy appearance.

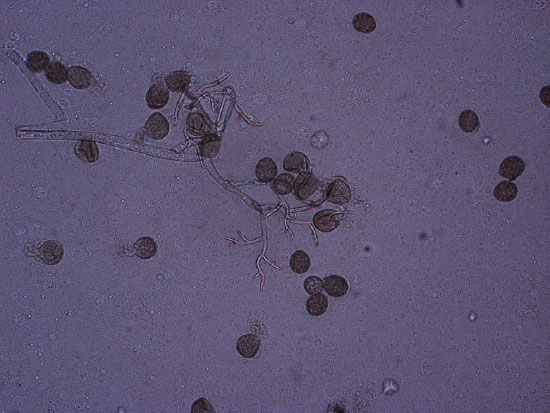

The spores (the oval, dark tan structures) are produced on sporangia (the clear, thread-like structures) on the underside of leaves.

It is unknown if the pathogen can survive the winter in Illinois. It is thought that it overwinters in greenhouses, or travels in on cuttings. The spores can travel large distances by wind. A small initial number of spores can quickly lead to a huge infestation.

Dr. Babadoost’s laboratory has been conducting experiments for the last 5 years to identify management options for basil downy mildew. Because this pathogen is known to develop resistance to fungicides quickly, chemicals with different modes of action should be used.

For commercial producers there are a few chemical fungicides that are very effective against this pathogen, but they require a pesticide applicator’s license and up to 17 applications a season. Oxidate (hydrogen dioxide), ProPhyt (potassium phosphite), K-Phite (mono- and di-potassium salts of phosphorus acid), Quadris (azoxystrobin), and Ranman (cyazofamid) are fungicides currently labeled for use in Illinois against downy mildew on basil and herbs. Revus was granted a Section 18 use permit in 2012 and 2013, but is not currently labeled for the 2014 growing season.

Chlorothalonil, a non-selective fungicide available under numerous trade names to individual gardeners, has been shown to be somewhat effective. Copper can also be used, but like chlorothalonil, it is not very effective.

Sanitation (removing and destroying diseased plants) is an important management technique. Plants should be carefully inspected at the nursery or garden store before being brought home. Because the pathogen needs moisture to thrive, reducing humidity and leaf wetness is important. Maximizing planting distances, planting in areas of full sun and air movement, and watering at the base of the plant are cultural techniques that can help reduce moisture on or around the plant, and help reduce disease. Dr. Babadoost reports that basil downy mildew is less virulent towards red or purple basil, which can be used as an alternative to the popular sweet basil. (Diane Plewa)

Author:

Diane Plewa